How “Screen Readers” Work: A Guide for Sighted Students and Allies

Imagine navigating the digital world not with your eyes, but with your ears and fingertips. For millions of people who are blind or have low vision, this isn’t an exercise in imagination; it’s their daily reality, made possible by an incredible piece of assistive technology: the screen reader. As sighted students and allies, understanding how these tools function isn’t just about technical curiosity; it’s a crucial step towards building a truly inclusive digital landscape for everyone. This guide will pull back the curtain on screen readers, demystifying their operations and empowering you to contribute to a more accessible future by designing and creating content that works for all users. It’s about fostering empathy and practical knowledge to bridge the visual gap in our increasingly digital lives.

Unveiling the Digital Navigator: How Screen Readers Transform Information

At its heart, a screen reader is a software application that interprets and conveys digital text and elements, usually through synthesized speech or a refreshable braille display. It acts as an intermediary between the user and the computer’s interface, allowing individuals who cannot see the screen to interact with operating systems, applications, and web content. Think of it as a specialized translator, converting the visual layout you take for granted into an auditory or tactile experience, providing independence and access to information for millions globally.

From Pixels to Pronunciation: The Core Function of Text-to-Speech

The most common output method for screen readers is text-to-speech (TTS). This technology converts written language into spoken words. When a screen reader encounters text on a webpage, in a document, or within an application, it sends that text to a TTS engine. The engine then synthesizes the speech, which the user hears through headphones or speakers. Users can typically adjust the speech rate, volume, and even the voice (male/female, different accents) to suit their preferences, often listening at speeds that might sound incredibly fast to a sighted listener—sometimes up to 400 words per minute or more. This high-speed listening is a learned skill, akin to speed reading, allowing efficient consumption of vast amounts of digital information. Modern TTS engines also strive for natural-sounding intonation and pronunciation, making the auditory experience more pleasant and understandable. Many screen readers offer a wide array of voices and languages, allowing users to personalize their listening experience significantly.

Beyond Sound: The Role of Refreshable Braille Displays

While speech is primary for many, some users, particularly those proficient in braille, prefer or supplement speech with a refreshable braille display. This device connects to the computer and features a line of pins that physically rise and fall to form braille characters, representing the text currently focused on by the screen reader. As the user navigates, the braille display updates dynamically, offering a tactile reading experience. This is especially valuable for proofreading, understanding complex formatting (like code or mathematical equations), or for users who prefer a silent reading method in public spaces. Braille displays come in various sizes, typically showing between 12 and 80 braille cells, and often include navigation buttons that mirror screen reader commands, providing an integrated tactile and interactive experience. They are a critical tool for literacy and precision for many blind users, offering a non-auditory alternative that can be crucial in certain professional and educational contexts.

The Invisible Bridge: How Screen Readers Interact with Your Computer’s Core

Screen readers don’t “see” the screen in the same way human eyes do; they don’t analyze pixels or interpret visual layouts. Instead, they rely on a sophisticated communication channel established between applications, the operating system, and the screen reader software itself. This channel is built upon what are known as accessibility APIs (Application Programming Interfaces).

Accessibility APIs: The Language of Digital Inclusion

Every modern operating system (Windows, macOS, Linux, iOS, Android) and many applications are designed with accessibility in mind, exposing their internal structure and content through these specialized APIs. When a developer builds an application or a website, they can ensure that meaningful information about elements (like buttons, links, headings, images) is exposed through these APIs. The screen reader then queries these APIs to understand:

- What is this element? (e.g., “This is a button,” “This is a heading level 1”)

- What is its role? (e.g., “clickable,” “editable,” “read-only”)

- What is its name/label? (e.g., “Submit button,” “Contact Us link”)

- What is its state? (e.g., “checked,” “collapsed,” “disabled”)

- Where is it in the document structure? (e.g., “This heading is followed by a paragraph and then a list.”)

Popular accessibility APIs include Microsoft’s UI Automation, Apple’s AX API, and the Linux Foundation’s AT-SPI. Understanding how these APIs function and how they are utilized by assistive technologies is key to grasping the technical backbone of screen reader functionality. Without proper implementation of these APIs by developers, screen readers would be unable to gather the necessary semantic information, rendering many applications and websites unusable for blind and low-vision users. This is why well-structured code is paramount for accessibility. Learn more about these crucial interfaces by exploring Understanding Accessibility APIs.

The Virtual Buffer: A Screen Reader’s Internal Map for Navigation

For complex content like webpages, screen readers often create an “off-screen model” or “virtual buffer.” This is an internal representation of the content that is structured for sequential reading and navigation, often different from the visual layout you see. Instead of trying to parse the visual arrangement of pixels, the screen reader uses the information exposed by accessibility APIs and the Document Object Model (DOM) to build a logical, linear representation of the page. This virtual buffer allows users to navigate a webpage in a structured manner, moving from heading to heading, link to link, or paragraph to paragraph, regardless of their visual placement. It effectively flattens the two-dimensional visual interface into a one-dimensional, navigable stream of information, making the content understandable and explorable through auditory or tactile means. This buffer is crucial for efficient content consumption, allowing users to quickly skim or dive deep into specific sections.

Navigating the Digital Realm: A Screen Reader User’s Journey

Interacting with a computer using a screen reader is a highly specialized skill, relying on a combination of keyboard commands and specific screen reader functionalities. Unlike sighted users who primarily use a mouse and visually scan content, screen reader users operate entirely through distinct navigation strategies.

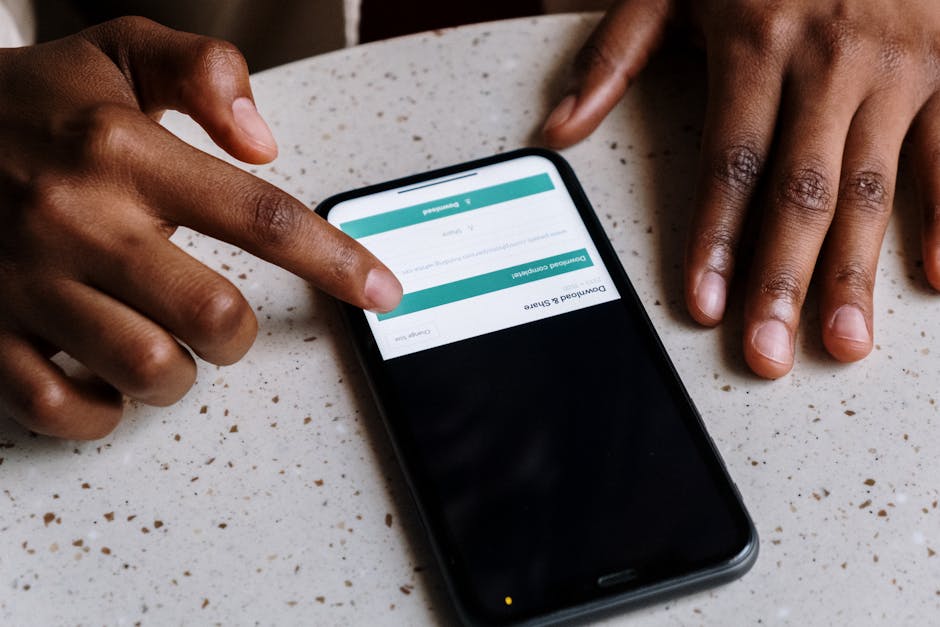

Keyboard Prowess: The Primary Interface

The keyboard is the screen reader user’s primary tool. Mouse interaction is generally impractical, as it requires visual coordination. Instead, users rely on a vast array of keyboard shortcuts, many of which are specific